The Underground Railroad, a network of safe havens that helped American slaves escape captivity, ran directly through New York City. In fact, the New York stops were an important junction on the journey to liberty. In dozens of homes, churches and businesses throughout the city, brave New Yorkers helped thousands of African American slaves escape to freedom.

Though slavery was abolished in New York in 1827, helping fugitive slaves was a dangerous undertaking. The city was divided between abolitionist and pro-slavery factions – sometimes violently. Slave hunters scoured the city to recapture fugitive slaves and occasionally kidnap free blacks. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 made assisting runaway slaves a crime. Out of safety, New York’s Underground Railroad was concealed.

While many of the “stations” of the railroad have been destroyed, you can still visit important sites of New York City’s Underground Railroad.

Manhattan Underground Railroad Sites

David Ruggles’ Home – Ruggles was the nation’s first black journalist and a zealous abolitionist. He founded the New York Committee of Vigilance, an integrated group that protected blacks from slave catchers. His home on Lispenard Street was a hub of the antislavery movement and a refuge for runaway slaves. Ruggles guided 600 slaves to freedom, including Frederick Douglass. 36 Lispenard Street, on the corner of Church Street. For more on Ruggles, see our post David Ruggles – NYC’s first Black Freedom Fighter.

Theodore Wright’s House – Revered Wright, the first African American to earn a degree in theology, preached against the evils of slavery. He worked closely with Ruggles to defend black Americans, and his home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. The building, built in 1809, is now an NYC Landmark (hosting a J. Crew boutique and liquor store). 235 West Broadway, on the corner of White Street.

143 Nassau Street – this building once housed the offices of the New York Anti-Slavery Society, the first national organization of its kind. Harriet Tubman sometimes stopped there to obtain train or boat tickets while escorting her “passengers” to freedom.

Bialystocker Synagogue – Before 1905 this historic synagogue was the Willett Street Methodist Episcopal Church. In a corner of what is today the women’s gallery there is an opening to a narrow shaft. Inside the shaft a ladder leads to the attic, where fugitive slaves were reportedly sheltered. 7 Willett Street.

Abigail Hopper Gibbons House – The Gibbons family were prominent abolitionists and their home harbored runaway slaves. During the Draft Riots of 1863, the house was attacked by an angry mob and burned. Two of the Gibbons daughters narrowly escaped through the roof and onto the adjacent homes. Unfortunately, the current owner has defaced the original facade and erected a fifth floor penthouse. While he wrangles with the Landmarks Preservation Commission, the building remains a construction zone behind scaffolding. 339 West 29th Street, between 8th & 9th Avenues.

Brooklyn Underground Railroad Sites

Brooklyn, with its bustling port full of ships from the American South and free black residents, was an important nexus on the “freedom trail.”

Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims – this progressive church was known as the “Grand Central Depot” of the Underground Railroad. The pastor was Henry Ward Beecher, whose dramatic sermons against slavery made him a celebrity. His performances became so famous that “Beecher Boats” ferried devotees across the East River, including Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, and Abraham Lincoln. Always a showman, Beecher staged mock slave auctions in the church, with the congregation bidding furiously to buy the captives’ freedom. Fugitive slaves were sheltered in the church basement before continuing to the next “station.” The church, which features an exhibit on Beecher and the congregation’s abolitionist history, is part of our Stroll Through Brooklyn Heights. 75 Hicks Street, Brooklyn.

Abolitionist Place – In 2007, the city renamed downtown Brooklyn’s Duffield Place as Abolitionist Place. The street includes two 1840s houses that are believed to have been stations on the “freedom trail.” The basement of 233 Duffield includes a capped well and exit shaft used when the house was “a feeding station” for escaped slaves. 227 Duffield was the home of staunch abolitionists Thomas and Harriet Truesdell, and its subbasement contains a sealed arch leading to a tunnel. The mysterious tunnel runs beneath Duffield Street and may have led to the Bridge Street African Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal Church, the first African-American church in Brooklyn and a known depot, two blocks away. 227 Abolitionist Place is now a small museum and cultural center.

Weeksville – a free African-American community that thrived from the 1840s through the 1930s. By the 1850s Weeksville was home to more than 800 residents and had its own elementary school, orphanage, churches, benevolent societies, and abolitionist newspaper. A census from the time shows that 30 percent of Weeksville’s black residents had been born in the South. Today, the Weeksville Heritage Center is a museum featuring three historic homes, a research center, and cultural programs and events. 1698 Bergen Street, between Rochester and Buffalo Avenues, Brooklyn.

Underground Railroad Memorials & Research

Harriet Tubman Memorial – a larger-than-life bronze sculpture of the famed Underground Railroad conductor who sometimes brought her “passengers” through New York City. The imposing sculpture stands on a traffic island at the crossroads of St. Nicholas Avenue, West 122nd Street and Frederick Douglass Boulevard in Harlem.

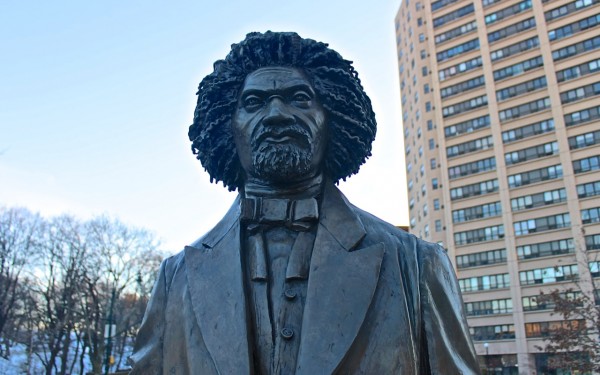

Frederick Douglass Memorial – located at the northwest corner of Central Park, the memorial honors the African-American abolitionist, orator, writer and statesman who escaped to freedom in New York City. There is an eight-foot bronze sculpture of Douglass as well as a fountain and granite blocks inscribed with biographical information and Douglass quotes. Central Park North (West 110th Street) and Frederick Douglass Boulevard.

There is a life-size bronze statue of Douglass outside the entrance of the New York Historical Society, which offers exhibits, artifacts, and online research related to New York’s Underground Railroad.

The Brooklyn Historical Society also offers a trove of information about Brooklyn’s Underground Railroad. Be sure to check out their current long-term exhibit, In Pursuit of Freedom, focused on Brooklyn’s anti-slavery movement.

Have you visited any of New York’s historic African-American sites? If so, tell about your experience in the comments below.