An African American defies discrimination, refusing to leave his seat on a train. He is forced out, and later sues the railway. Amazingly, this occurred in 1841…114 years before Rosa Parks would not be moved. The courageous man was David Ruggles, a major figure in the American antislavery movement and the nation’s first black journalist and printer.

Ruggles was born in Connecticut in 1810 to free black parents. He arrived in NYC in 1827 (the year New York abolished slavery), 17 years old, brash, educated, and seemingly fearless. After a stint as a mariner, he opened his own grocery store, which he turned into the nation’s first black bookshop. It was attacked and burned by a white mob.

Ruggles soon became involved in the city’s abolitionist movement, writing hundreds of antislavery editorials, letters and pamphlets advocating “practical abolitionism,” which included civil disobedience and self-defense. He urged,” let us in every case of oppression and wrong, inflicted on our brethren, prove our sincerity, by alleviating their sufferings, affording them protection, giving them council, and…prove ourselves practical abolitionists.” Ruggles also advocated bringing more women into the movement.

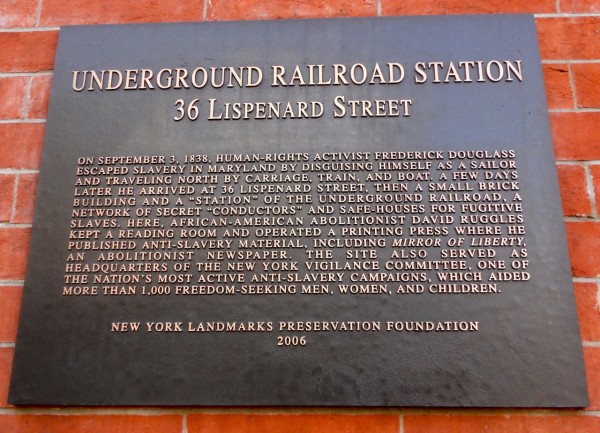

From his home at 36 Lispenard Street, he opened another bookstore and circulating library (blacks were restricted from “Reading Rooms”), which became a hub for abolitionists. He operated the first black-owned printing press and published his own works, including Mirror of Liberty, the first black magazine.

Ruggles did more than promote assistance – his home was a station on the Underground Railroad, the network that sheltered slaves escaping to freedom. Ruggles estimated he guided 600 slaves, including a troubled young runaway named Frederick Bailey. During Bailey’s stay, Ruggles educated him about abolitionism, shared his library, and even hosted Bailey’s wedding. Ruggles gave Bailey a letter of recommendation and a five-dollar bill when he left the city. Once established in Massachusetts, Bailey began a new life with a new name – Frederick Douglass.

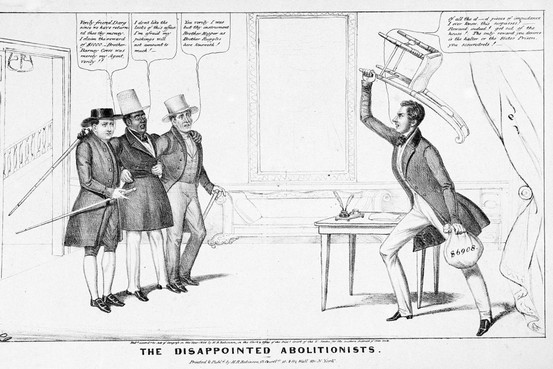

NYC was a dangerous place for blacks in the early 19th Century. Slave catchers (known as “blackbirders”) roamed the streets looking for runaway slaves, and often kidnapped blacks off the street (fugitives and free) to be sold into captivity. To combat this, Ruggles helped organize the New York Committee of Vigilance, an integrated group that protected blacks, physically and legally. He demanded the city grant jury trials for the abducted, and obtained lawyers for them. This was dangerous work, and Ruggles was often beaten and jailed. Despite the personal cost, he would not be deterred.

A notable example of Ruggles’ protection was the Darg Case, in which he intervened between Darg and his slave, who sought asylum in NYC. When Ruggles refused to turn over the fugitive, Darg charged him with grand larceny, and the press portrayed the Committee as extortionists. In another case, Ruggles had a ship captain arrested for slave trading. The captain, a slave catcher, and a police officer tried to abduct Ruggles from his home and ship him south for sale into slavery. Frustrated by Ruggles’ escape, the captain demanded Ruggles’ arrest on grounds that he resembled a runaway slave.

The stress and beatings took a toll on Ruggles’ health, and by the age of 28 he suffered from severe intestinal disorders and was almost blind. In 1842 for left NYC for Florence, Massachusetts, where he helped establish “a depot for fugitives” and a place of “equal brotherhood.” He died of a bowel infection in 1849.

During his short life, Ruggles inspired many abolitionists, including William Cooper Nell, Sojourner Truth, and of course, Frederick Douglass, who eulogized Ruggles saying, “He has literally worn himself out in humanity’s struggle…his loss is irreparable. We look in vain for another to fill his place.”