Harlem isn’t just one of the most historic neighborhoods in New York City. It’s also one of the liveliest.

The word “Harlem” alone evokes images of legendary nightspots like the Cotton Club, where great musicians filled the night with hot jazz. For others, it brings thoughts of the notorious ghetto: decrepit, dirty, and crime-ridden.

While both are part of its past, Harlem today has entered a new era. Yes, Harlem is still a bit rough around the edges, with some abandoned buildings, poverty, and litter. But the streets are now safe, and many of Harlem’s architectural treasures have been restored. New restaurants, stores, and hotels are opening—and thriving.

The takeaway? Harlem is managing to maintain its unique culture while evolving into a vibrant, diverse community. And the time to visit Harlem… is now!

History of Harlem

Founded by Dutch settlers in the 1650s, Harlem was a rural village for an entire two centuries.

When railroads linked Harlem to the city in the 1870s, though, buildings sprang up—including tenements for immigrants in the east, and elegant row houses in the center for affluent whites.

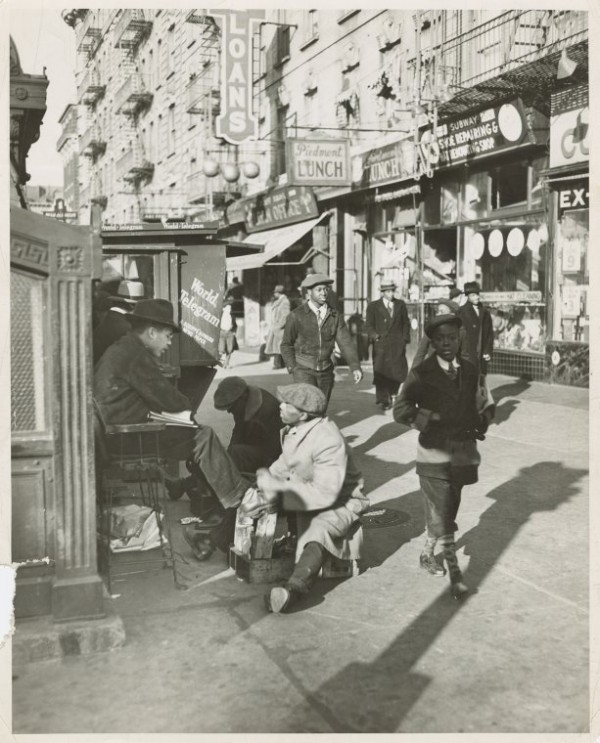

At the turn of the century, the coming of the subway led to a building boom that went bust, leaving blocks of houses and apartments empty. New York City’s African-American residents moved uptown. Soon, Harlem was the “Black Capital of America.”

The Harlem Renaissance flourished in the 1920s, when the “New Negro” produced exceptional art, literature, poetry, theater, and, of course, music. People flocked to nightclubs like the Cotton Club and the Savoy Ballroom to hear jazz by Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Cab Calloway.

But the Great Depression devastated Harlem, and later race riots inflicted great damage on the neighborhood. Decades of poverty and neglect left Harlem a dangerous, decaying ghetto.

In the 1990s, people began buying and restoring Harlem’s brownstones. The city renovated abandoned buildings for affordable housing, and folks moved to the neighborhood for its reasonable rents.

While the recession has slowed development, today, a new renaissance is well under way in Harlem.

A Harlem tour

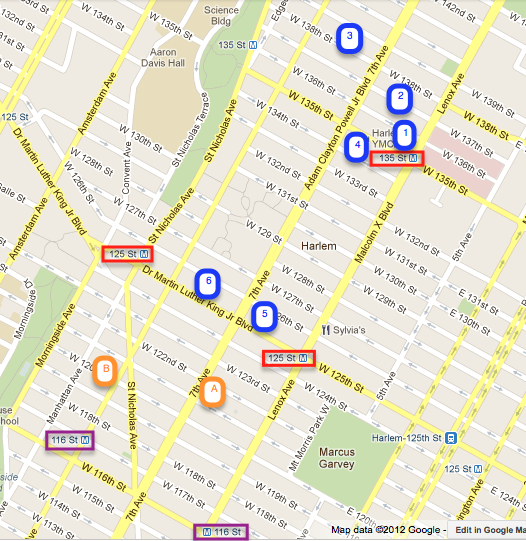

Want to explore Harlem? Just remember that New York actually has several Harlems, stretching across the Manhattan river to the river above Central Park. There’s East Harlem (Spanish Harlem, or “El Barrio”), which occupies Fifth Avenue to the East/Harlem River, and West Harlem, which includes the neighborhoods of Morningside Heights and Hamilton Heights.

This tour focuses on Central Harlem, the historic center of African-American culture in New York (and America!).

1. Take the #2 or 3 subway to the 135th St. stop.

The block of 135th Street to the west (between Lenox Ave. and Adam Clayton Powell Blvd.–look for the YMCA) was one of Harlem’s first African-American enclaves. This is where Philip A. Payton broke the color barrier by offering apartments to NYC’s Black citizens—their first decent housing in the city’s 250-year history.

The northwest corner of this intersection was once Speakers’ Corner, where charismatic activists like Marcus Garvey and A. Philip Randolph extolled passersby from atop their soapboxes.

The northwest corner of this intersection was once Speakers’ Corner, where charismatic activists like Marcus Garvey and A. Philip Randolph extolled passersby from atop their soapboxes.

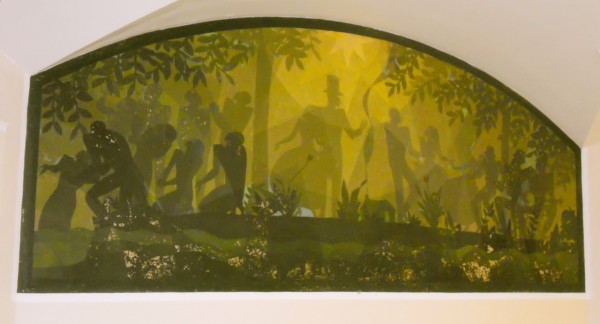

The large brick building is the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the nation’s largest research library devoted to cultures of people of African descent. The Center also presents exhibits, performances, forums, and events showcasing Black culture. Look in the library for the four Aaron Douglas murals, which typify the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance. (Plus, there are convenient restrooms near the entrance doors!).

Across Lenox Ave is Harlem Hospital, where Martin Luther King, Jr. was saved after being stabbed by a deranged Harlemite. Reproduced on its new, glass-encased wing is a montage from the hospital’s historic WPA murals, which will be restored and displayed in the new building. The figure in white is Cab Calloway “beatin’ the band.”

2. Take a brief detour west on 136th Street to see #107 and #111, brownstones converted into an evangelical church and a funeral home, respectively. The “garden level” and/or basements of many Harlem brownstones were converted into funeral parlors, houses of worship, shops, bistros, intimate clubs—and, during Prohibition, speakeasies!

Return to Lenox and continue to 138th Street, then turn left and walk west.

3. The Abyssinian Baptist Church is at 132 W. 138th Street.

Founded in 1808 by African Americans and Ethiopian merchants unwilling to accept the segregated seating of other churches, the Abyssinian (which refers to the ancient name for Ethiopia) is one of the nation’s oldest, most influential African-American congregations.

Since erecting this church in 1923, the Abyssinian has been a force for social justice and economic development in Harlem. The church is often closed to the public, so attending a Sunday service may be your only option for entrance. Be sure to read the Abyssinian’s instructions for first-time visitors before attending.

The decaying brick buildings at Adam Clayton Powell and 138th St. were the location of the crack den in Spike Lee’s film “Jungle Fever.” But they also were once the Renaissance Ballroom and Casino, a Black-owned entertainment complex that included a movie theater, ballroom, billiards parlor, and space for sporting events. During its heyday in the 1920s, “the cream of Harlem” held social events here, revelers danced the Charleston and Black Bottom, and America’s first African-American professional basketball team, the Harlem Renns, played here. It also hosted performances by Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and Ella Fitzgerald.

It’s now owned by the Abyssinian Development Corp, who plan to incorporate the façade into a modern residential tower.

3. At Adam Clayton Powell and 139th Street, turn left (west) onto Strivers Row, the two-block stretch of row houses with two unique features: their elegant, unified designs, and the private alleys behind each row (rare for New York!). Architect Stanford White designed the row on the north side of 139th Street.

Built in 1891, most of these homes remained empty until affluent African Americans (Strivers) bought them in the 1920s. Eubie Blake, W.C. Handy, Fletcher Henderson, and Alpha Phi Alpha (the nation’s first black fraternity) all resided on the row.

Wander along the block to Frederick Douglass Blvd. The street comes to an abrupt end with a park a block and a half west. This is St. Nicholas Park, which is built on the massive ridge of Manhattan bedrock that separates Harlem Heights from the plain of Harlem. The large Gothic building on the summit is City College.

Walking south down the boulevard, you can look into the private alley between the row houses of 139th and 138th Streets. At the corner, turn left and walk east on 138th St. to see more of “the Row.” Note Victory Tabernacle Church, built into a narrow townhouse plot, the mid-block alley gateway that still reads “walk your horses,” and #237, which is abandoned and boarded-up.

Turn right, and continue south for three blocks on Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Blvd.

4. At 135th Street, you’ll see the large, historic Harlem YMCA (#181), where writers Claude McKay, Langston Hughes, and Ralph Ellison once lived, Jackie Robinson coached local kids, and James Earl Jones, Alvin Ailey, and Sidney Poitier performed in the Little Theater.

Just inside the lobby, look for Aaron Douglas’ 1933 mural, “The Evolution of Negro Dance”—unprotected in a children’s playroom! Heading back to the corner of Adam Clayton Powell, you’ll find an old wooden newsstand selling publications intended for African-American readers.

Walk south for 10 blocks on Adam Clayton Powell Blvd. At #2283, Hats by Bunn sells designer hats, which are quite popular with Harlem ladies for church attire.

The block of W. 133rd Street to your left was known as “Swing Street,” because it was lined with clubs, speakeasies, and after-hour hangouts. At #2271 is the Shine Bar/Restaurant, a popular jazz and world music club. A typical hair-braiding salon is at #2253, and #2251 is an African Caribbean Market, selling imported foods and African movies on DVD.

On the avenue’s island at 131st Street is the brightly colored marker where the Tree of Hope once stood. Performers at the famed Lafayette Theater (formally at 132nd) believed the tree bestowed good luck. Its stump is now in the wings of the Apollo Theater, where performers touch it before taking the stage.

Beginning at the southwest corner are a number of Public Housing towers (or “projects”) covering five city blocks.

At the southwest corner of 126th Street is the Alhambra Ballroom, which opened in 1905 as a lavish vaudeville theater. The ballroom was added in 1926, and featured performances by Bessie Smith, Jelly Roll Morton, and Billie Holiday.

5. 125th Street is the Harlem’s historic commercial heart. On the northeast corner is the behemoth Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building, with the statue of its preacher and statesman namesake. The open plaza is often the site of community gatherings, including the celebration of President Obama’s election, a vigil for Michael Jackson, and numerous political/civil demonstrations.

Across 125th Street at #132 is the huge Koch & Co. Building, a 19th-century dry-goods/department store from the street’s first glory days. Beside it is the Studio Museum in Harlem, dedicated to the works of Black artists, from the 19th Century to contemporary. The museum features a permanent collection, exhibitions, and events; it also has a nice café, and free admission on Sundays.

At the southwest corner is the Hotel Theresa, known as the “Waldorf Astoria of Harlem.” It’s hosted celebrities like Joe Louis, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and stars of the Apollo Theater. Many civil rights leaders also had offices in the hotel, including A Philip Randolph and Malcolm X.

And Fidel Castro checked in here while attending a U.N. session (he’d been evicted from a midtown hotel for keeping live chickens in his room!).

6. The Apollo Theater’s slogan, “where legends are made,” is no empty boast. This is where Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, James Brown, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Jimi Hendrix, Stevie Wonder, and the Jackson Five launched their careers.

It’s also launched some of the greatest stars of jazz, R&B, and hip-hop. Built in 1914 as a burlesque house for a whites-only audience, the theater still hides racy murals behind the red-velvet wall coverings. In 1934, it became the “125th Street Apollo,” a variety music hall open to everyone.

Today, the raucous Amateur Night at the Apollo (where so many stars have been discovered!) still takes place every Wednesday night. Excellent historic tours of the theater also are available by advance reservation.

After shopping on 125th Street, you can catch the subway one block west at St. Nicholas Ave. (for the A, B, C, D lines), or head back to Lenox Ave for the 2 or 3 lines (not to mention to check out three excellent restaurants: the acclaimed Red Rooster, Chez Lucienne, and Corner Social).

Want to keep going? Great! You can also…

A. Walk south down Lenox Avenue, lined with incredible brownstones and churches (in various states of repair), all built for a wealthy German-Jewish community in the 1880s. Turn left, or east, on 122nd St. (once called Doctors’ Row) to see beautiful homes leading to Marcus Garvey Park.

Return to Lenox via 121st St. On 116th St. is the site of Malcolm X’s mosque and the Malcolm Shabazz Harlem Market, where vendors sell authentic African handicrafts. From here, you can catch the subway, or continue six blocks south to Central Park and Harlem Meer.

B. Continue south down Frederick Douglass Blvd., where you’ll find the Harriet Tubman monument, and plenty of new, high-end businesses, including W’s chic Aloft Hotel, Harlem Vintage wine store, Patisserie des Ambassades, Levain Bakery (some say with the city’s best cookies), and Harlem Tavern. The subway stop is at 116th St.

Want more of Harlem?

Join the community in celebrating annual events like the African American Day Parade or Harlem Week, when 135th Street, from Lenox to St. Nicholas Avenue, is taken over by local shops, entertainment, plenty of soul food, and impromptu dance parties.

Please note: Visitors flock to Harlem Church services seeking an authentic cultural experience (which it certainly is!). However, it’s important to remember that these are religious services, and not simply a music performance. The congregations are devout, and take their worship seriously.

Therefore, it’s appropriate to dress conservatively, and never behave in a manner that is distracting to others. Visitors must arrive on time and remain for the entire service. Talking and taking photos or video recording are not acceptable. In addition to Abyssinian Baptist, visitor-friendly churches include Greater Refuge Temple, Mount Neboh Baptist, and United House of Prayer for All People.